-

Better BP®There’s a better way to capture BP—discover the keys to more accurate measurements.

Better BP®There’s a better way to capture BP—discover the keys to more accurate measurements. -

Exam Room DesignBetter exam room designs help create better care experiences for patients and staff.

Exam Room DesignBetter exam room designs help create better care experiences for patients and staff. -

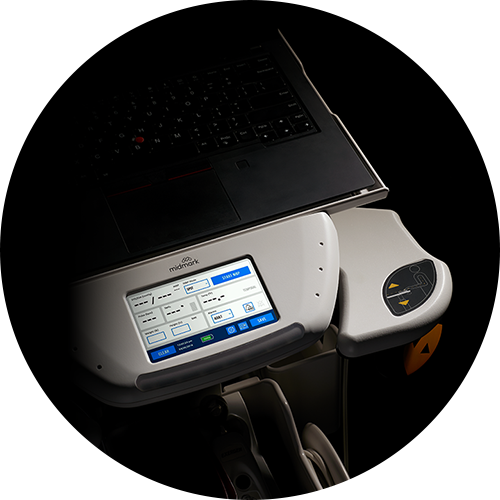

Medical Diagnostics Connected SolutionsThis is your go-to source for exploring, implementing, and supporting connected diagnostics.

Medical Diagnostics Connected SolutionsThis is your go-to source for exploring, implementing, and supporting connected diagnostics. -

Workflow OptimizationDesign a more efficient, effective healthcare experience.

Workflow OptimizationDesign a more efficient, effective healthcare experience. -

Asset Tracking + ManagementEnsure that your caregivers readily have the assets they need while better controlling costs.

Asset Tracking + ManagementEnsure that your caregivers readily have the assets they need while better controlling costs.

-

Patient AccessibilityLearn more about the 2024 US Access Board Standards (MDE) and what makes the Midmark 631 + 626 compliant.

Patient AccessibilityLearn more about the 2024 US Access Board Standards (MDE) and what makes the Midmark 631 + 626 compliant. -

Patient + Staff SatisfactionSet the foundation for happier, more content patients and staff.

Patient + Staff SatisfactionSet the foundation for happier, more content patients and staff. -

Patient + Staff SafetyCreate a safer healthcare environment for patients and staff.

Patient + Staff SafetyCreate a safer healthcare environment for patients and staff.

Government Solutions

-

Architectural ResourcesVisit our planning and design library for the architectural resources you need.

Architectural ResourcesVisit our planning and design library for the architectural resources you need. -

Design for the Point of CareLet us help you design a more efficient, effective healthcare experience.

Design for the Point of CareLet us help you design a more efficient, effective healthcare experience. -

Exam WorkflowsBetter care starts with a better exam workflow space. We can help.

Exam WorkflowsBetter care starts with a better exam workflow space. We can help. -

Procedures WorkflowsResponding to patient demands while controlling costs requires greater efficiency in the procedures room workflow.

Procedures WorkflowsResponding to patient demands while controlling costs requires greater efficiency in the procedures room workflow. -

Vital Signs WorkflowsEnhance caregiver-patient interaction and improve outcomes at the foundation.

Vital Signs WorkflowsEnhance caregiver-patient interaction and improve outcomes at the foundation. -

Instrument Processing WorkflowStandardize the flow of instruments to reduce contamination and improve efficiency.

Instrument Processing WorkflowStandardize the flow of instruments to reduce contamination and improve efficiency.

Synthesis® Cabinetry Catalog

Explore our digital catalog for available products and part numbers.

Learn more

Rethinking the Exam Room - AIA Credit

The course is delivered live by Midmark clinical design consultation experts. It provides healthcare architects and designers who are AIA members a high-level view of how proper exam room design can improve clinical workflow efficiency at the point of care.

Learn more

Featured Product

Midmark® 631 Procedure Chair

The right procedure room equipment can make a crucial difference in both patient outcomes and caregiver safety. Particularly for patients...

2025 Promotions

-

2025 Point of Care Exam Room PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here.

2025 Point of Care Exam Room PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here. -

2025 Examination Chair Trade-In PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here.

2025 Examination Chair Trade-In PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here. -

2025 Vital Signs Device PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here.

2025 Vital Signs Device PromotionThe order period has ended, but you can still claim your incentives through February 27, 2026. Redeem here.

2026 Promotions

-

2026 ECG Trade-In PromotionSave $200 when you trade in an ECG for a new Midmark® Digital ECG—and save $50 more when you upgrade with a DICOM license.

2026 ECG Trade-In PromotionSave $200 when you trade in an ECG for a new Midmark® Digital ECG—and save $50 more when you upgrade with a DICOM license. -

2026 Procedure Chair Trade-In PromotionGet up to $850 back + an additional $150 with delivery and trade-in removal services.

2026 Procedure Chair Trade-In PromotionGet up to $850 back + an additional $150 with delivery and trade-in removal services. -

2026 Examination Chair Trade-In PromotionRebates up to $500 + a Bonus $150 with delivery and trade-in removal services.

2026 Examination Chair Trade-In PromotionRebates up to $500 + a Bonus $150 with delivery and trade-in removal services. -

2026 Sterilizer Trade-In PromotionSave up to $500 when you trade in a sterilizer and purchase an eligible Midmark model.

2026 Sterilizer Trade-In PromotionSave up to $500 when you trade in a sterilizer and purchase an eligible Midmark model. -

2026 Sterilizer Maintenance Kit PromotionPurchase a Next Generation Midmark® M9 or M11 Steam Sterilizer, register the device and receive a free Sterilizer Maintenance Kit.

2026 Sterilizer Maintenance Kit PromotionPurchase a Next Generation Midmark® M9 or M11 Steam Sterilizer, register the device and receive a free Sterilizer Maintenance Kit.

-

InfographicsLet us show you the whole picture with real-world applications.

InfographicsLet us show you the whole picture with real-world applications. -

Published PerspectivesChange is a constant in healthcare – and we’re leading the way. Read our recent bylines and articles.

Published PerspectivesChange is a constant in healthcare – and we’re leading the way. Read our recent bylines and articles. -

BlogLet’s talk about better care. Join the discussion today.

BlogLet’s talk about better care. Join the discussion today. -

Medical Press ReleasesFind out what’s happening at Midmark. View the latest news about Midmark and the healthcare industry.

Medical Press ReleasesFind out what’s happening at Midmark. View the latest news about Midmark and the healthcare industry.

Education

Services

-

Consulting ServicesLet us help you make data-driven decisions to improve patient flow and clinical processes.

Consulting ServicesLet us help you make data-driven decisions to improve patient flow and clinical processes. -

Delivery + Installation ServicesMidmark Delivery Services will professionally manage your Midmark equipment shipping, delivery, staging and installation for maximum project success.

Delivery + Installation ServicesMidmark Delivery Services will professionally manage your Midmark equipment shipping, delivery, staging and installation for maximum project success. -

Product Repair + Service SolutionsExplore available support and services plans to help keep your medical equipment and devices operational.

Product Repair + Service SolutionsExplore available support and services plans to help keep your medical equipment and devices operational.

Support

-

Product Manuals (Technical Library)Visit our technical library for product manuals and more.

Product Manuals (Technical Library)Visit our technical library for product manuals and more. -

Shop Parts, Software + ServicesVisit The Online Parts Store for 24/7 ordering.

Shop Parts, Software + ServicesVisit The Online Parts Store for 24/7 ordering. -

Technical Support | MedicalLet our dedicated technical service team help you find parts, documentation and more.

Technical Support | MedicalLet our dedicated technical service team help you find parts, documentation and more. -

Customer ExperienceOur friendly support team is here to assist you every step of the way.

Customer ExperienceOur friendly support team is here to assist you every step of the way.